Guillermo del Toro Is Good, but Andy Warhol Already Made One of the Strangest Adaptations of Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’

There’s always been something cinematic about the ache inside the story of Frankenstein — that blend of awe and rot. Clearly, that’s what attracted Guillermo del Toro to the property. His cinematic worlds — from Pan’s Labyrinth to Crimson Peak — bleed sympathy for the monstrous, turning horror into heartbreak the way The Shape of Water turned loneliness into devotion. That same empathy can be found in films like Edward Scissorhands or TV shows like Penny Dreadful – stories in which the monster is not the threat, it’s a mirror on us. So for a filmmaker like del Toro, that kind of storyline is the one that creeps into his notebooks, a misunderstood creature still waiting for someone to love it properly.

But long before the “elevated horror” crowd started waxing poetic about empathy and trauma, another vision of Frankenstein crawled out of the grave — half-camp, half-corruption, and entirely off its rocker. Paul Morrissey’s Flesh for Frankenstein didn’t whisper about sorrow —it screamed through a haze of pop-art decadence, sex, and aristocratic decay. Imagine Hammer Horror spliced with A Clockwork Orange, then pushed through the sleaze filter of Rocky Horror Picture Show — that’s where this thing lives. It’s Frankenstein stripped of remorse and dipped in irony, a fever dream where art meets exploitation and science becomes sin.

A Frankenstein for Andy Warhol’s Factory

In the early 1970s, the cultural electric hum of Andy Warhol’s Factory and its fringe cinema was still buzzing with collapse and excess. Into that realm stepped Paul Morrissey, the director previously known for gritty contemporaries like Flesh and Trash. With Flesh for Frankenstein (also marketed as Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein), Morrissey re-appropriates the Shelley myth not as melancholic romantic tragedy, but as a cynic’s cabaret of body horror and cultural rot.

Warhol’s involvement? Minimal. According to sources, the “Warhol” tag was largely a branding gambit—Warhol dropped by, lent his logo, and walked away. Morrissey ran the set, scripted the madness, and stitched together the monstrosity in Italy with an Italian crew. The result is a Frankenstein story that wants less to mourn the monster and more to measure how far the monster might go: How roomy the body can become for society’s neuroses. How far the aristocrat can stray from science to vengeance. How the myth of life-making can turn into a spectacle of control, sex, and decay.

From Midnight Movie to Arthouse Ancestor

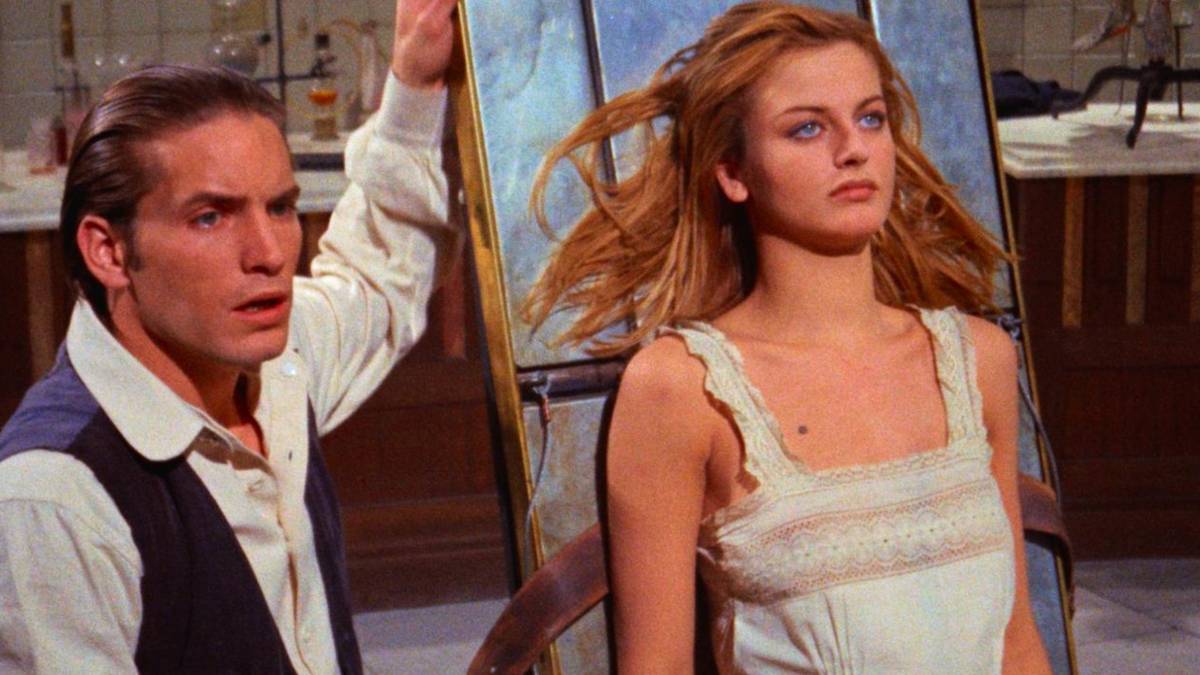

Morrissey’s twist is wild on the page: Baron von Frankenstein (played by Udo Kier) is married to his sister, and together they’re obsessed with creating a “perfect Serbian race” from stitched body parts. Bodies arrive in crates. Organs launch toward the camera in 3-D. Status, bloodline, sexual repression, and violence swirl like a toxic cocktail. The film embraces aristocratic rot with the same relish as poor bourgeois guilt. In one scene, it’s not the monster’s longing for humanity that resonates—but the aristocrat’s longing for perfection and the twisted idea that to make life is to master flesh, not heal it. The Frankenstein myth becomes an elite joke (and a nasty one) about bodies owned, manipulated, and disposed. This is where del Toro’s sensibility would diverge: his monsters weep. They ache. They carry hope or heartbreak. Morrissey’s monster laughs—or sputters in agony, sure—but the laughs are inside the torture. The horror is the joke. Yet the sensibility is connected: both filmmakers sense the monster as an extension of creator guilt, of human failure, of unsated longing. They just arrive at opposite ends of that spectrum.

At the time of its release,Flesh for Frankensteinwas a midnight-movie spectacle in 3-D — yes,the gore even leaped off the screeninto the audience’s laps. Its X-rating, itsscandalous orgy of sex and dismemberment, its absurdity—all made it fringe. But that fringe is now the kind of ancestry that arthouse horror traces back to.Morrissey took cues from his exploitation rootsyet welded them to pop-art irony: he cast the myth in neon death, not candlelit tragedy. Critics later noted the film’s “assured sense of camp”—the self-aware ribbing of the Frankenstein myth while delivering the visceral shocks.That means today’s indie horror, the one comfortably museum-screened or Criterion-curated, owes a nod to this kind of boundary-blurring. Morrissey did not soften the monster for empathy, but opened the myth to absurdity—andin doing so, made the myth adaptable again.

‘Flesh for Frankenstein’ Is Strange, Funny, and Far Less Polite Than Most Frankenstein Adaptations

Here’s the rub: Flesh for Frankenstein isn’t polite. It doesn’t wrap the creature in tragedy and tears. It forces you to feel weird in your seat. The Baron doesn’t chant, “I want to love my monster.” He snarls: “To know death, Otto, you have to f**k life in the gallbladder!” The film is deliciously grotesque. It turns the myth into a carnival of decomposition and desire, aristocrat style. And still, if you squint, you see the same impulse del Toro carries. A fascination with creation and destruction. A sense that the monster is us. That the experiment on flesh is an experiment on the soul. Morrissey just cuts out the sentimental soundtrack and replaces it with industrial laughter. Thinking now about how a del Toro version might feel: lush, mythic, romantic, tragic. Meanwhile, Morrissey’s is cold, synthetic, perverse, and hilarious. Two Frankenstein visions, chasing the same ghost in divergent ways.

In the end, if you love the idea of Frankenstein as broken-hearted birth and creature longing, del Toro is the call. But if you want a Frankenstein that laughs in the darkness, that slurps up aristocratic guilt and hurls organs at the camera, then Morrissey’s Flesh for Frankenstein is the weird, chaotic precursor you need. It reminds us that the monster myth isn’t just about sorrow—it can be one hell of a prank.

Flesh for Frankenstein is available to stream on Pluto TV.